“Anderson continues to imbue her work with a singular perspective that is both haunting and timeless.”

-The New Yorker

Iconic performance artist Laurie Anderson expands upon her work fusing storytelling and technology, creating an installation and performance piece that examines lost identity, memory, and the resiliency of the human body and spirit.

This gripping new artwork interweaves film, sculpture, music, and video to examine the story of Mohammed el Gharani, one of the youngest detainees at Guantanamo Bay. Open to the public during the day, HABEAS CORPUS encourages visitors to use the drill hall as place to meditate on time, identity, surveillance, and freedom. The evocative environment within the drill hall includes an original, immersive soundscape that blends guitars and amps in feedback, originally designed by Lou Reed, with sounds derived from audio surveillance and nature. The space will also be activated by improvised music performances throughout the day and concludes at night in a celebratory concert and dance party with Syrian singer Omar Souleyman, Merrill Garbus of tUnE-yArDs, multi-instrumentalist Shahzad Ismaily, guitarist Stewart Hurwood, and Anderson herself.

The installation also includes additional film installations including From the Air, which explores the impact of global events on daily life and resonates with many of the themes explored in el Gharani’s story.

The result is a groundbreaking new work that spans the worlds of visual art, performance, and experimental music as created by one of America’s most renowned and daring artistic pioneers.

FACT SHEET: Mohammed el Gharani and Guantànamo Bay

- Mohammed el Gharani was among the youngest prisoners in Guantànamo Bay, sent to the prison camp in 2002 at 14 years old.

- Mohammed was held at Guantànamo without charge or trial for over seven years (2002-09) and tortured while in US detention.

- In January 2009, Judge Leon of the US federal court dismissed the evidence against Mohammed and ordered his immediate release. Judge Leon found that the evidence against Mohammed was largely derived from prison informants; inconsistent and contradictory within itself, and unreliable.

- Mohammed grew up in Saudi Arabia, after his parents migrated from Chad in search of a better life. He suffered discrimination as a Chadian, and was denied schooling. As a child, he worked as a street salesman to support his family.

- Mohammed was desperate to get some kind of education and improve his life. He saved the money he earned, and at 14 years old travelled to Pakistan to study English and computers with a friend’s uncle who ran a school there.

- While praying in a mosque, Mohammed was rounded up and arrested by Pakistani police and handed to US forces. As a fan of American movies, he was optimistic that the Americans would treat him well and release him.

- Mohammed was taken to Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan, where he was kept naked for days and racially abused. One of the first words that he learned in English was “nigger.”

- After two months of detention in Afghanistan, Mohammed was transferred to Guantànamo Bay in 2002.

- Mohammed was abused so badly that he tried to commit suicide twice while in Guantànamo. He was deprived of sleep and repeatedly moved between cells to prevent him from resting. He was kept in freezing conditions and constantly blasted with music and strobe lights. Guards slammed Mohammed’s head to the floor, breaking two teeth. An interrogator stubbed out a cigarette on his arm.

- Mohammed was falsely accused of fighting for the Taliban in Tora Bora and being a member of a London-based al-Qaeda cell. He had never visited either Afghanistan or the UK. The allegations were flat wrong.

- The evidence used to keep Mohammed in Guantànamo Bay for over seven years was based almost entirely on statements from two other prisoners. Those statements were eventually shown to be unreliable; the US government stopped using them and dropped the allegations about Mohammed.

- Mohammed was sent to Chad in June 2009. He had never been to Chad, but Saudia Arabia, his birth country, refused to accept him because of his ethnic background. Having missed out on a high school education, he loves reading, particularly about history.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: Mohammed el Gharani and Guantànamo Bay

1. Does the US federal habeas corpus judgment in Mohammed’s case mean that he is innocent?

Yes. The ruling is as close to a proclamation of innocence as a court gets. Judge Leon found that the US did not have evidence to justify even arresting Mohammed in the first place- let alone enough to charge him or convict him.

2. Why was Mohammed sent to Guantanamo Bay?

Mohammed was sold to the US by Pakistan. In the panic following 9/11, the US military paid Pakistanis and Afghans vast bounties to hand over ‘suspicious’ people, especially foreigners and strangers. 85% of Guantànamo prisoners were sold to the US for a bounty. The DOD then tortured these people to extract intelligence. This led to vast swathes of faulty intelligence, including false confessions, which was used to justify holding prisoners like Mohammed. Emil Nakhleh, a CIA intelligence operative sent to Guantànamo at the very beginning to assess what was hoped to be an intelligence goldmine, interviewed a number of prisoners and assessed that a large number of them should never have been there in the first place. Mohammed el Gharani was one of those prisoners.

3. Was there any evidence against Mohammed at all?

No. The intelligence presented as evidence against Mohammed was false. The US no longer alleges that Mohammed has ever been involved with terrorism. Their evidence came from two notorious informants who fabricated vast swathes of information about fellow prisoners for their own gain. The intelligence was eventually reviewed by a federal judge who rejected it as entirely unreliable. Because of Mohammed’s case, the US later had to stop relying on these serial informants in other cases.

4. What do the ‘Wikileaked’ government files say about Mohammed?

Mohammed is mentioned in a 2011 Wikileaks ‘document dump’ of 779 old US military intelligence files about Guantànamo prisoners. These files are hosted on the New York Times website and are often the first page to appear when googling a detainee’s name. The files are largely discredited, and no longer relied upon even by the US government departments who created them. They contain the original false allegations about many detainees, including Mohammed, which were based on faulty intelligence debunked years ago, either by US federal courts or by the US military itself. As attorney John Sifton told the Miami Herald: “There’s a lot of debunked information in these documents that the government itself doesn’t even hold to anymore. In some respects what we’re seeing is a snapshot of the United States government’s beliefs from seven years ago.” In addition, the Bush Administration set up administrative procedures for the military to use to determine eligibility for release from Guantànamo Bay: the Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) and later Administrative Review Board (ARB). The results of these procedures are publically available and hosted on the New York Times website. Like the Wikileaks documents, they are based on early assessments of the Guantànamo detainees which contain unsubstantiated, discredited and false information collected through the unreliable statements of informants, torture, or other forms of coercion. The large-scale discrediting of both these sources has been widely reported.

5. Why are Guantànamo prisoners barred from entering the US?

This is a blanket ban imposed by the US government on all ex-Guantànamo prisoners. It has nothing to do with guilt or innocence and is applied across the board.

6. How did the US government get its information so wrong?

There are four main reasons that the US ended up with so much bad information relating to Guantànamo prisoners.

- The US relied on bounties – not intelligence or battlefield capturesMost Guantànamo detainees (85%) were not captured by U.S. forces on the battlefield. They were picked up from their homes, from mosques or from the street by local Afghans or Pakistanis, and sold to the US for bounties.

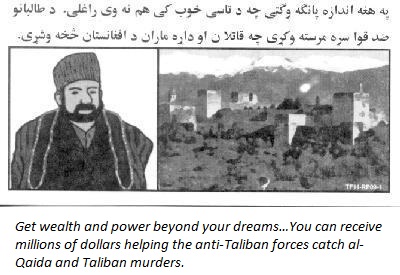

In the panic following 9/11 attacks, American airplanes flew over Afghanistan and Pakistan dropping fliers promising $5,000 for foreigners handed over to them. Here is an example:

This sum of money would be life-changing for Pakistani or Afghan villagers, amounting to several times the average annual wage. With everything to gain and no set standards of what might constitute a ‘terrorist suspect’, there was huge pressure on Afghan and Pakistani villagers to turn in any foreigner for immense sums of money. Former Pakistani president Musharraf discusses this in his autobiography:”We have captured 689 and handed over 369 to the United States. We have earned bounties totalling millions of dollars. Those who habitually accuse U.S. of not doing enough in the war on terror should simply ask the CIA how much prize money it has paid to the Government of Pakistan.”The result was that many innocents were caught up the US dragnet. CIA intelligence officer Emile Nakhleh, who interviewed a random sampling of detainees to assess the supposed ‘intelligence gold mine’ transferred to Guantànamo stated:”And then I concluded that some people – many of those who were there [in Guantànamo], really should not have been there. They were part of the dragnet. And frankly had the United States had not paid the Pakistanis for every guy they got, most of them would not have been there. And in fact, in the beginning when I came back and gave a high-level briefing, some of our very senior people did not like the briefing at all because they said, ‘they are guilty. That’s why they are there.’ I said ‘Now that’s kind of circular logic, isn’t it?’ And the point was that unfortunately I was proven correct. And the reason I say that is because more than 500 people were release. And obviously if they were terrorists they would not have been released.” - The US government relied on tortureThe US system for separating ‘the wheat from the chaff’ was extremely poor. Having cast their dragnet over Pakistan and Afghanistan, the DOD and CIA did not have the intelligence, expertise or skill to separate those involved with Al-Qaeda/Taliban from harmless foreigners, such as refugees or migrant workers. The bounty system was no substitute for long-term, hard-won human intelligence.So the US resorted to torture and abuse. The Bush administration signaled that the Geneva Conventions ‘did not apply’ to prisoners captured in the ‘war on terror’, and a secret program of rendition and torture began. Hundreds of men were transferred to US black sites like Kandahar and Bagram and were tortured mercilessly to extract information. Techniques included: prolonged naked exposure to the freezing Afghan winter, severe and repeated beatings, electric shocks, shackling in stress positions, sexual and other forms of humiliation, deprivation of food and sleep and desecration of the Quran, as well as other forms of torture highlighted in the US Senate Torture Report. Alex Gibney’s documentary film ‘Taxi to the Dark Side’ shows how an innocent taxi driver’s legs were beaten so hard for so long that they became literally pulp, and he died from his injuries.The bipartisan report by the Senate Armed Services Committee on detainee treatment is one of the clearest sources for information on the US’ torture techniques as used in Guantànamo Bay. According to the summary:

“The abuse of detainees in U.S. custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of ‘a few bad apples’ acting on their own…The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees.”It is therefore no surprise that many of the men held sought to tell their interrogators whatever they wanted to hear. As a result, detainees ‘admitted’ to a vast array of improbable crimes and/or implicated their fellow detainees, earning themselves a one-way ticket to the newly-established Guantànamo Bay prisons. This junk ‘intelligence’ – a toxic mixture of abuse, bias, and hearsay from jailhouse snitches – made its way into Defense Department intelligence analysis documents, where it was used to justify prisoners’ detention for years.Thus Guantànamo was filled with ‘chaff’ — low-level and no-level people. The original institutional mistakes then compounded themselves, as inexperienced Defense Department interrogators came under enormous pressure to get these people to give up information about terrorism – information the vast majority of these prisoners simply did not have.As early as December 2002, reports were coming out that many of those held at Guantànamo had no connection to the Taliban or Al-Qaeda. As the LA Times reported:”Maj. Gen. Michael E. Dunlavey, the operational commander at Guantànamo Bay until October, traveled to Afghanistan in the spring to complain that too many “Mickey Mouse” detainees were being sent to the already crowded facility, sources said… The sources blamed a host of problems, including flawed screening guidelines, policies that made it almost impossible to take prisoners off Guantànamo flight manifests and a pervasive fear of letting a valuable prisoner go free by mistake.” - The US relied on incompetent interrogatorsThe faulty intelligence-gathering did not end once men were transferred to Guantànamo. Colonel Brittain Mallow, who served as the commander of the unique Criminal Investigation Task Force, a unit of military investigators formed in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks to prepare criminal cases against suspected terrorists, is clear about the level of incompetence of the interrogators:The military and intelligence personnel who were there, I firmly believe didn’t know what they were doing…The other interrogators who were there for the large part had not had any experience in actual interrogations…In early days, if you asked me if people crossed the line, I think it was routine. People were experimenting. They were trying whatever they thought would work .Torin Nelson, an interrogator at Guantànamo confirms the level of inexperience among the interrogators:”I just believe that a lot of the other individuals [interrogators] that were there really shouldn’t have been there. That they weren’t prepared for it. That they did not have the background, the knowledge, the insight, the expertise, a lot of it on the leadership side… for example, the FBI, one of my counterparts knew nothing about Afghanistan. I mean when the detainee was talking about major cities in Afghanistan-Mazar-I-Sharif we were talking about the transit of the captured prisoners across Northern Afghanistan, from Kunduz Province over to Sheberghan Prison by the Uzbek commander, Rashid Dostum. All this stuff should have been common knowledge to an FBI interrogator. And yet, he had no idea where Mazar-I-Sharif was or how to spell it, or anything about it. So, if you don’t know anything about what you’re supposed to question on, how are you going to question about it?”

- The US relied on incentivized informantsThe US routinely relied on informants to provide testimony against other Guantànamo detainees, incentivizing them with various perks. US courts have since determined that testimony from these informants is completely unreliable. McClatchy reported that the testimony, “…of just eight detainees was used to help build cases against some 255 men at Guantànamo – roughly a third of all who passed through the prison. Yet the veracity of the testimony of many of them was later questioned.”Judge Leon, the judge in Mohammed’s habeas hearing, dismissed the government’s case against him on the basis that all the so-called evidence against him came from two unreliable informants. His ruling states:”Unlike most of the other cases reviewed to date by this Court, the Government’s evidence against el Gharani consists principally of the statements made by two other detainees while incarcerated at Guantànamo Bay. Indeed, these statements are either exclusively, or jointly, the only evidence offered by the Government to substantiate the majority of their allegations. In addition, unlike the other cases reviewed by this Court to date, the credibility and reliability of the detainees being relied upon by the Government has either been directly called into question by Government personnel or has been characterized by Government personnel as undetermined.”

BACKGROUND: GUANTÀNAMO BAY

In January 2002, Guantànamo Bay detention center received its first group of 20 detainees when a plane from Afghanistan landed in Cuba. The detention center has housed 780 detainees in total. However, it has long been apparent that few detainees are linked to terrorist or combatant activities.

Currently, there are 114 detainees left at Guantànamo, nearly half of whom have been cleared for transfer. The prison remains open despite the fact that one of President Obama’s first pledges on assuming the United States Presidency in 2009 was to close the prison in Guantànamo within one year. It continues despite its illegality and the fact that Guantànamo Bay’s stark realities have been on the public record for years. They are well-documented in the first-hand accounts of detainees, testimonies of guards and officials, and numerous reports and legal cases.

Despite an increasing recognition of mistakes made by the Bush and Obama administrations in the context of the ‘war on terror,’ men from Guantànamo continue to live with having been labelled the ‘worst of the worst.’ People still presume their guilt. It is a stigma that is hard to overcome.

Guantànamo by Numbers

- Current detainee census: 114, from 17 countries.

- Captives approved for transfer or repatriation to their homelands: 52.

- Captives now designated as “forever prisoners,” indefinite detainees under the Law of War, without charge or trial: 32.

- Detainees who died in the camps: Nine.

- First captives: 20 arrived Jan. 11, 2002 to inaugurate Camp X-Ray.

- Last known arrival: Muhammed Rahim al Afghani, on March 14, 2008.

- Last detainee release: Four cleared prisoners to Afghanistan Dec. 20, 2014.

- Last detainee resettlement: Six Yemenis to Oman June 12, 2015

- Largest current concentration of captives, by nationality: 75 Yemenis. Followed by Saudi Arabia, 10 citizens, Afghanistan, eight.

- Prisoners convicted by Military Commission: Four. Four men who had been earlier convicted were subsequently cleared through appeal.

- Prisoners currently facing a Military Commission: Seven.

- U.S. Supreme Court cases involving detainee rights during the War on Terror: Three.

- Times the justices sided with detainees against the Bush administration: Three.

- Total number of detainees held at Guantànamo in the war on terror: At least 780, with the Senate ‘Torture Report’ revelation that Ibn al Shaykh al Libi, ISN212, was held at a CIA prison there.

- Cost to house each detainee each year: $3.2 million.

BACKGROUND: ABUSE AT GUANTÀNAMO

The US took advantage of the fact that detainees would not fall within the jurisdiction of the American civil courts by developing systems of interrogation banned under national and international human rights and humanitarian law.

A Memorandum dated October 11, 2002 sought approval for the use of three categories of treatment in interrogation.

Category II tactics included the use of dogs, removal of clothing, hooding, stress positions, isolation for up to 30 days, 20-hour interrogations, and deprivation of light and auditory stimuli. Category 3 tactics included the ‘use of scenarios designed to convince the detainee that death or severely painful consequences are imminent for him and/or his family,’ and ‘use of a wet towel and dripping water to induce the misperception of suffocation’.

The treatment of detainees at Guantànamo has been universally criticised by various international bodies. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in its Resolution 1433 concluded that ‘many if not all detainees have been subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment occurring as a direct result of official policy.’ Juan Mendez, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture also stated in October 2013 that he “considers the practice of indefinite detention, other conditions applied to them [Guantànamo detainees] such as solitary confinement, as well as the use of force feeding as forms of ill-treatment that in some cases can amount to torture.” Furthermore, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has repeatedly asked the U.S. to ensure that they “investigate and punish all instances of torture and other ill treatment” and to “respect the ban on using any statement obtained under torture in any legal proceeding(s).”

In a 2006 report, the UN Committee Against Torture stated that the United States should cease to detain any person at Guantànamo Bay and “take immediate measures to eradicate all forms of torture and ill-treatment of detainees.” Further, it said that the United States ‘should rescind any interrogation technique – including methods involving sexual humiliation, ‘waterboarding,’ ‘short shackling’ and using dogs to induce fear … in all places of detention under its de facto effective control.’

In a report produced in 2006, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) concluded that the interrogation techniques authorised by the Department of Defense amounted to degrading treatment in violation of Article 16 of CAT and Article 7 of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

A particular feature of the Guantànamo regime was the involvement of health professionals in detainee’s abuse. Doctors and psychologists were present during torture and ill-treatment, denied medical care to detainees, provided confidential medical information to interrogators, and failed to stop or document abuse.

BACKGROUND: THE LEGAL SITUATION AT GUANTÀNAMO

Guantànamo Bay has been repeatedly described as a legal black hole. It is no coincidence that it is housed in Cuba. Pentagon lawyers theorized that detainees at Guantànamo Bay could be held entirely outside the jurisdiction of US civilian courts and therefore beyond the rule of law. And by creating the extra-legal category of “enemy combatants” the US would ensure that that the detainees were outside the reach of international law as codified in the Geneva Conventions.

Under the US Constitution and centuries of US law, it is the government’s job to prove someone guilty if it wants to take his freedom away. That premise is the basis of our democratic system. The basic assumption at Guantànamo-that the men there are ‘guilty until proven innocent’-turns hundreds of years of the American legal system on its head.

It was not until 2004-two years after the opening of the prison-that the Supreme Court ruled that for jurisdictional purposes Guantànamo was functionally part of the United States. It was only at that time that lawyers were first able to access the prison and represent the men held there.

With the exception of 15 prisoners who have faced or are facing the military commission system, the US has never charged any of the prisoners with a crime. With no charges, there can be no trial. With no trial, there is never formal recognition of exoneration. All prisoners were categorized as “enemy combatants”-a made-up category under international law which denied them the status of ‘prisoner of war’ as laid out in the Geneva Conventions. The military denied detainees the right to a civilian or military trial and created special courts called the Military Commissions.

Only eight prisoners (1% of the total prison population) were ever convicted through the Military Commission system. Of those, four have had their convictions overturned.

Due to the weakness of the case against him, Mohammed never faced a Military Commission. The closest that men like Mohammed ever came to a trial were their Habeas Corpus hearings. Mohammed won his Habeas Corpus hearing very easily.